After Muslims ruled Spain for centuries, the city of Toledo was taken by Christian forces in 1085. Even after it became Christian, scholars there continued studying Arabic. Toledo became an important centre for translating Arabic books into Latin.1

Toledo: Inspiration for Quran Translation

In the 1100s, Peter the Venerable (Peter of Cluny) visited Toledo. He believed Christians did not understand Islam properly. He wanted to refute Islam and protect Christians from being influenced by it. So he sponsored the first full Latin translation of the Quran. Peter did not know Arabic nor did he try but he lead a group of translators to work on a number of projects. The most important project was the Quran translation which was led by the Robert of Ketton. Robert was an English scholar and translator who lived in 12th century Spain. He worked closely with Arabic-speaking scholars and was skilled in mathematics and astronomy as well as languages. He was part of the wider translation movement in Toledo, where many scientific and religious works were being translated from Arabic into Latin. The translation was completed in July of 1143. This translation became a starting point for the Western study of Islam, and it was fuelled by anti-Muslim polemics. It is interesting that in earlier centuries, those who sought to refute the Quran invested years studying it in Arabic. Today, opposition is often less intellectual and more performative like burning it, a very different kind of engagement.

Ketton’s translation of the Quran was important, but it had problems. It was not a careful, word for word translation. He changed the order of chapters, shortened some verses, expanded others, and tried to make the Arabic sound like elegant Latin. It was more of a paraphrase than an exact translation. Still, it became the main version used in Europe for hundreds of years. Martin Luther, a seminal figure in the Protestant Reformation, remarked that the Quran should be published in Arabic because it would reveal itself to be a forgery, and that publishing a translation of the Qur’an was the most damaging thing that could be done to Islam. How wrong he was!

Later, during the 1500s and 1600s, other scholars tried to improve on this work. But none produced a fully detailed and scholarly treatment of the Quran.

The city of Toledo was under Muslim control from 711 until 1085

Lodovico Marracci: A Turning Point

A major change came with Lodovico Marracci (1612–1700). He was an Italian Catholic priest and scholar. Whilst studying Greek and Hebrew in Rome, he came across a page written in an unknown language. Standing next to him was a Maronite scholar (probably linked to Syria) who told him it was Arabic and that he should learn it.

It was well known that many Levantine Christians were in Rome, as the Catholic Church was making more of an effort in the 16th century to train Arab Christians. There was even a Maronite College for Syrian Christians to train. Rome, for the better, became a place to learn Arabic, and many from across Europe came to study Arabic there.

Marracci lived in Rome and was dedicated to learning the language. At first, he received help from fellow Arabic-speaking Christians, which helped him master it. This expertise in Arabic would change his life, and in 1645 he began translating the Bible into Arabic. Marracci remained in Rome for the rest of his life, and he was appointed Chair of Arabic at the University of Rome.

In 1698 he published Alcorani Textus Universus. The reason was to unmask Islam as a heresy. As he mentions in the introduction, “I attack the enemies with their own weapons.” He relied heavily on the Tafsir al-Jalalayn, Zamakhshari, and Baydawi. His work was so detailed that some of his friends claimed it would actually be dangerous for Christians, as the commentators often explained what appeared to be contradictions in the Quran.

His work was in two large volumes:

- The first volume explained Islam and tried to refute it.

- The second volume included the full Arabic text of the Qur’an, a Latin translation, detailed notes, and a refutation of every surah.

Even though his goal was polemical, his scholarship was serious and detailed. His translation was much more accurate than Robert of Ketton’s. Later European translations, including George Sale’s English translation (1733), depended heavily on Marracci’s work.

Because of this, Marracci shaped how Europe understood the Quran for many generations.

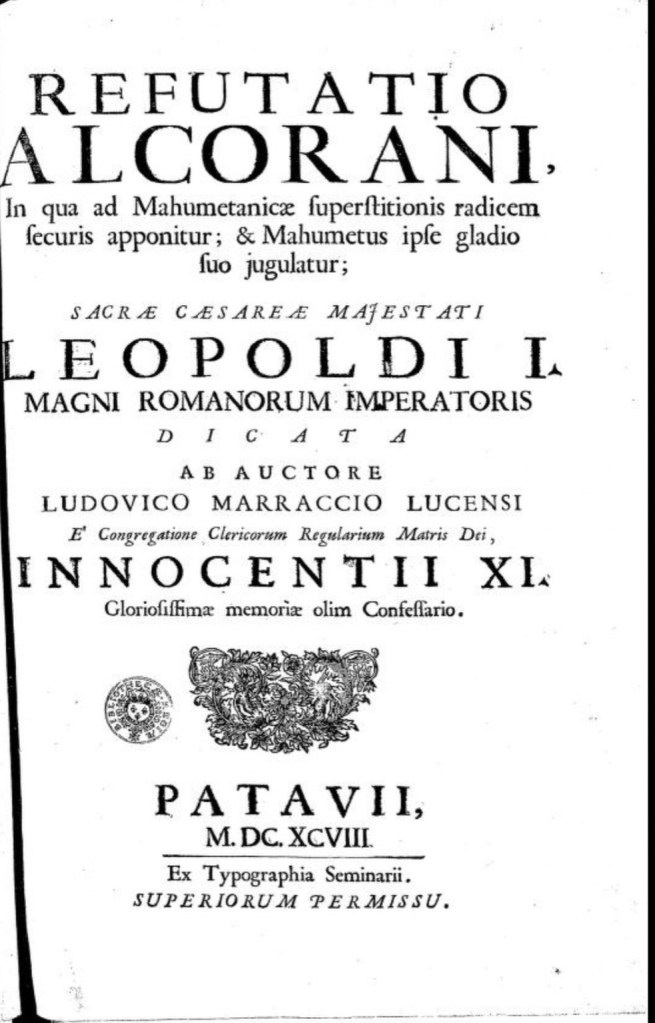

“Refutatio Alcorani” (Padua, 1698), A Vatican backed Latin edition by Lodovico Marracci, dedicated to Emperor Leopold I. Written to challenge Islam, yet it became one of the foundations of Western Qur’anic scholarship.

Below is a translation of the Marracci’s title page:

REFUTATION OF THE QUR’AN

“In which an axe is laid to the root of the Muhammadan superstition; and Muhammad himself is slain by his own sword.”

Dedicated to

His Sacred Imperial Majesty

Leopold I,

Great Emperor of the Romans,

By the author

Lodovico Marracci of Lucca,

Of the Congregation of the Clerics Regular of the Mother of God,

Former Confessor of Innocent XI of glorious memory.

Published at Padua, 1698 (MDCXCVIII)

From the Seminary Press.

With permission of the superiors.

Marracci dedicated this work to the Habsburg Emperor Leopold I, who defeated the Ottomans at Vienna in 1683. The Ottomans were led by Kara Mustafa Pasha on behalf of Sultan Mehmed IV. This marked the end of Ottoman expansion to the West. The Ottomans and the Habsburgs were in perpetual war for European domination. The Habsburgs considered themselves the Roman Empire from the time of Charlemagne, whereas the Ottomans considered themselves the vanguards of the Muslims.

Marracci to Sale: The Quran in English

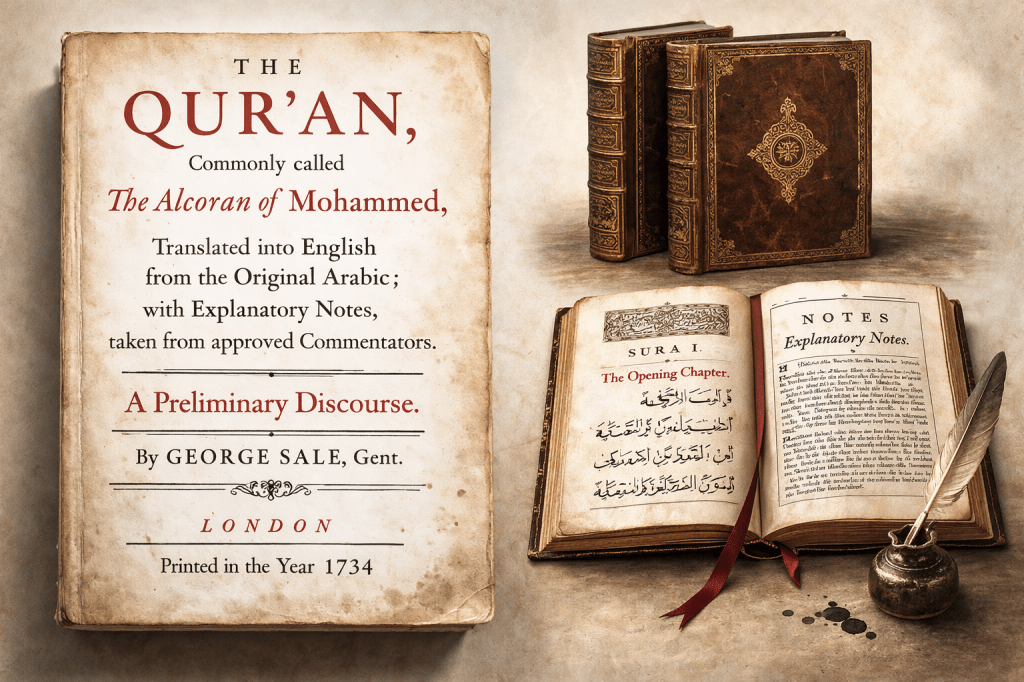

George Sale (1697–1736) published an English translation of the Qur’an in 1734. There are two theories regarding how Sale became acquainted with Arabic: (i) he was taught Arabic by Arab Christians, or (ii) he taught himself the language. Sale relied heavily on Marracci’s scholarship of the Quran.

George Sale did not simply translate the Quran from a standard Arabic copy of the text. Instead, he likely relied on the famous Quranic commentary written by Baydawi, which includes the full Quranic verses alongside detailed explanations. This means that when Sale translated, he was probably reading the Quran through al-Baydawi’s commentary rather than from a plain Quran manuscript. An important clue lies in the textual variants he followed. There were small differences in how certain verses were written or read in different manuscript traditions, and the version Sale used matches the readings found in Baydawi’s commentary rather than the standard Ottoman Qur’an text commonly used in his time. This strongly suggests that Sale worked directly from a copy of Baydawi’s commentary held at the Dutch Church (Austin Friars) in London. In other words, Baydawi’s work was not just a tool for interpretation but likely the actual base text from which Sale produced the first major English translation of the Quran.

George Sale’s 1734 English translation of the Qur’an

Sale was more measured in his dealing with Islam and Muslims compared to Marracci, who saw his endeavour as an exposition of Islam at a time when Christianity had triumphed over Muslim powers. Sale writes, “If the religious and civil institutions of foreign nations are worth our knowledge, those of Mohammed, the lawgiver of the Arabians, and founder of an empire which in less than a century spread itself over a greater part of the world than the Romans were ever masters of, must needs be so.”

From Sale to the Modern Day: The Flourishing of English Quran Translations

Many English translations appeared after Sale. However, it was not until 1920 that the English convert Marmaduke Pickthall produced the first faithful English version of the Quran intended for believers. He was followed by many others, and in the last few decades we have seen a remarkable number of translations being produced. Among them is The Majestic Quran by Dr Musharraf Hussain (Al-Azhari). The Majestic Quran offers three new perspectives that had not been presented before. (i) The author adds over 1,400 subheadings, allowing the reader to understand when the subject changes. (ii) His English is not archaic and is very accessible. (iii) His scientific and traditional background allows readers to appreciate the depth with which he explains certain natural phenomena, often supported by scientific explanations.

Imam Baydawi: Marracci, Sale, & Shaykh Gibril Haddad’s Engagement

As mentioned, Marracci heavily depended on various manuscripts of Baydawi. His aim was to offer a brutal exposé of the Quran through one of its most prolific commentators. Sale entirely based his translation on the manuscript of Baydawi that he had access to. The question does arise: who is Baydawi, and why is he so important?

- This article draws inspiration from the chapter “The Qur’an in Translation” in The Republic of Arabic Letters: Islam and the European Enlightenment by Alexander Bevilacqua. ↩︎