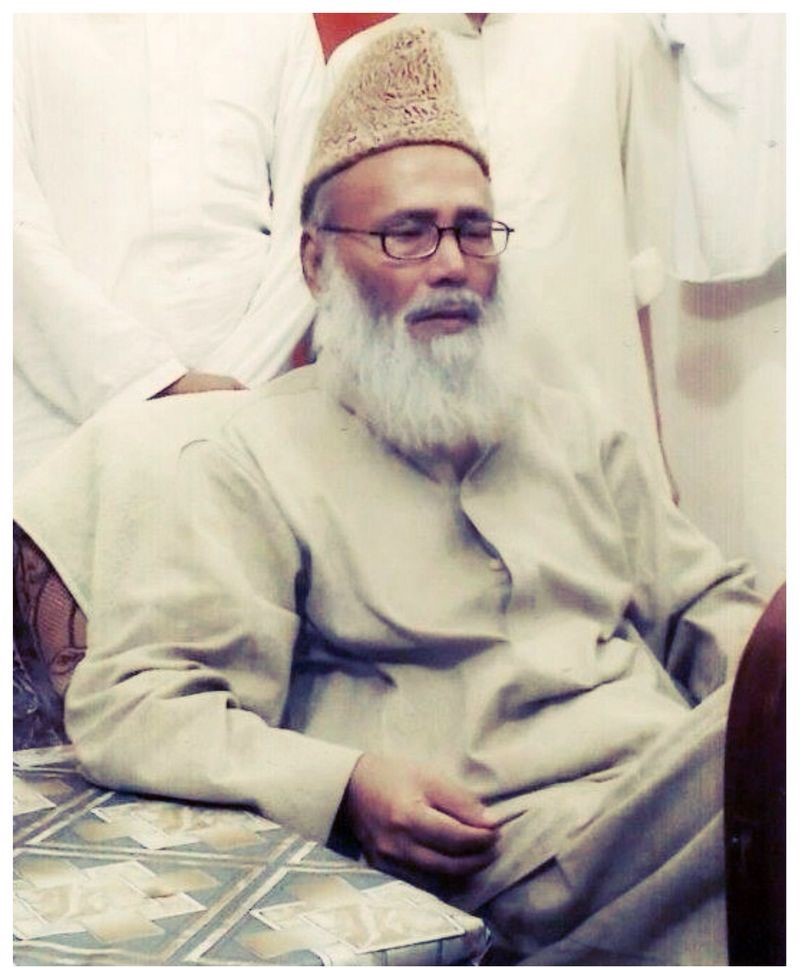

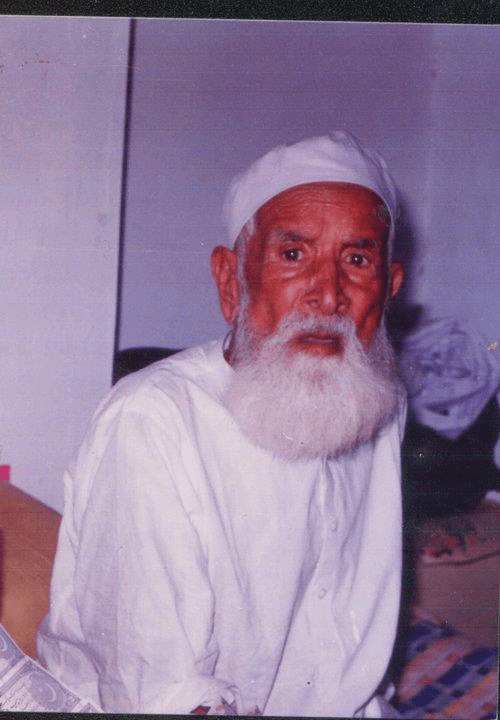

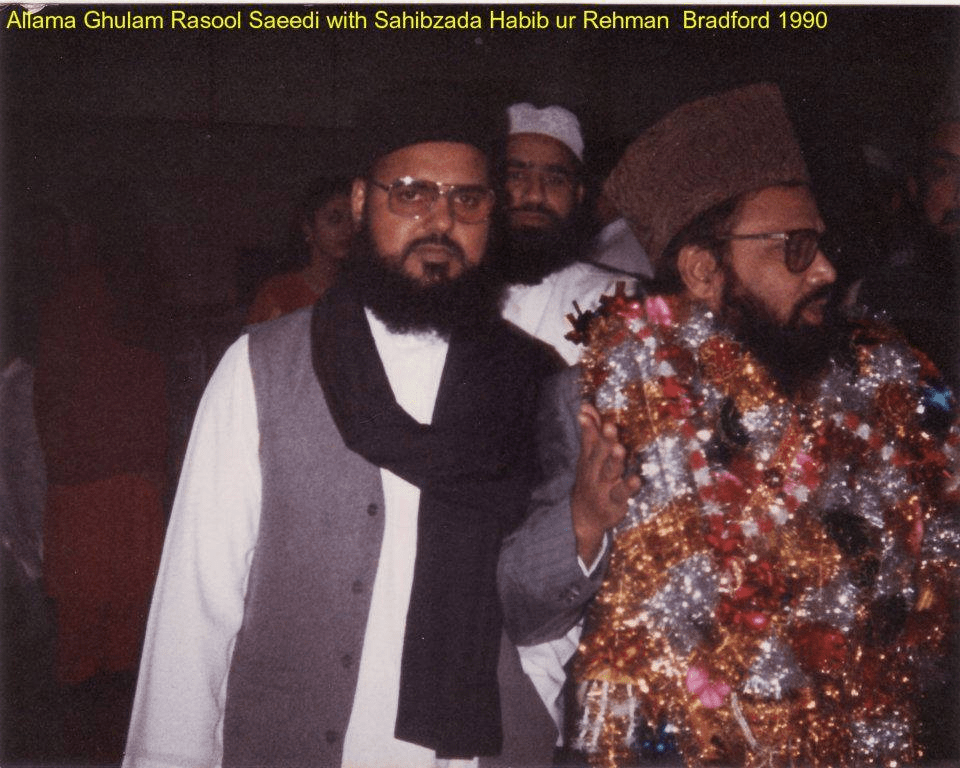

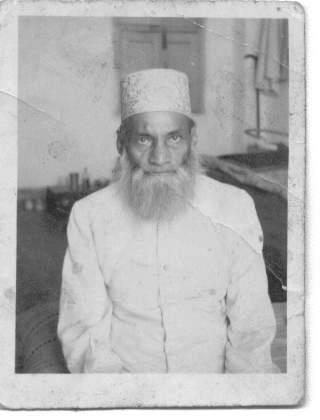

On the 4th of February 2016, a day still vivid in my memory, I checked my WhatsApp messages and was shocked to learn that Allamah Saʿīdī had passed away. My hands trembled, tears filled my eyes as I absorbed the news. The person whose books I had directly benefited from, along with thousands of other scholars, was no more. I had never met Allamah Saʿīdī, nor had I heard any of his talks. My only connection with him was through his writings. I faintly remember a radio interview in 2004 during my internship at the Bobbersmill Community Centre (Nottingham), where Allamah Saʿīdī discussed Fiqh issues with Imam Safiullah on Radio Dawn. It was only later, upon reading his books, that I truly understood who Allamah Saʿīdī was.

In this brief piece, my aim is to present the biography of Allamah Saʿīdī and introduce some of his notable works.1

Allamah Saʿīdī’s childhood

Born on 14th November 1937 in Delhi, India, Allamah Saʿīdī’s original name was Shamsuddin Najmi. His mother affectionately addressed him as ‘Najmi, my son’ in her letters. As he embarked on his religious education, Allamah Saʿīdī changed his name to Ġulām Rasūl Saʿīdī. His father, Muhammad Muneer, passed away during Allamah Saʿīdī’s childhood. Muneer had owned a press company in Delhi. After his death, Allamah Saʿīdī’s mother, Shafīq Fāṭima, remarried. She was a devout and God-conscious woman, devoted to performing the Tahajud prayer regularly. Shafīq Fāṭima played a pivotal role in teaching Allamah Saʿīdī and his siblings how to recite the Quran. With remarkable dedication, she would often recite 17 Juz of the Quran in a single day. In later years, as she lost her sight and hearing, she lamented her inability to recite the Quran. Shafīq Fāṭima passed away in August 2003 at the age of 86, leaving behind a legacy of piety and devotion.

Allamah Saʿīdī completed the recitation of the entire Qurʾān at the age of 6 with his mother. At the age of ten, he completed his primary education in Delhi and after the partition of India he moved with his family to Karachi (Pakistan). He completed a few years of secondary education and then began to work for a publication house.

Allamah Saʿīdī lived an extremely comfortable life in Delhi as his father owned a press company. Allamah Saʿīdī had a personal driver who would travel with him. However, after the passing away of his father things drastically changed. In Pakistan, his mother re-married and the house too small for all the family to stay in. Allamah Saʿīdī moved into a separate accommodation with his younger sister. During the day Allamah Saʿīdī would work and would leave his sister under the supervision of his neighbours. On one occasion, due to excessive flooding, a snake bit Allamah Saʿīdī’s sister due to which she passed away. She was only 14 years of age at the time. Allamah Saʿīdī was extremely fond of her and loved her. In later days he would often remember her and cry. Due to poverty, Allamah Saʿīdī moved to different accommodations and worked in a variety of different jobs. He worked at a hotel for some time, working during the day and sleeping in the hotel lounge during the night. After leaving the hotel job he would sell ice creams on a small stand in the streets of Karachi.

Allamah Saʿīdī’s educational journey

After work Allamah Saʿīdī would often go to the mosque to rest. The Imam there would only allow students to use the fans. Due to the intense heat, Allamah Saʿīdī would enter the mosque and read Qurʾān along with its translation just so he could use the fan. After listening to a talk of one of the great scholars of his age, Shaykh Muhammad Umar Icharvi2, Allamah Saʿīdī developed a deep yearning to study Islam. When he would read the Qurʾān, he would often get confused with different translations and would often ponder which translation was the correct one. He resolved to study Islam so he could remove such doubts.

One day, whilst selling ice cream on a hot day in Karachi, Allamah Saʿīdī came across a poster on the wall. As it was an extremely hot day, he did not receive any customers. So, he began to read the poster on the wall. The poster advertised that applications to study Islamic studies had opened at the Jamiya Muhammadiyya Rahim Yaar Khan seminary and that students who enrolled will receive free education, free meals and free accommodation. Looking at this poster, Allamah Saʿīdī was amazed that everything was free. Determined to confirm if this was actually true, he wrote a letter to the seminary and addressed it to principal, Shaykh Muhammad Nawāz Owaisī asking if what was advertised was indeed true. The Shaykh, acknowledging the passion of Allamah Saʿīdī wrote back saying that whatever was advertised on the poster was true. The Shaykh instructed Allamah Saʿīdī to travel immediately to the seminary, although classes were scheduled to start in a month’s time. The Shaykh advised Allamah Saʿīdī to borrow the money for travel and that once he arrives at the seminary, he would be given his travel fair. Allamah Saʿīdī returned his ice cream stand to its owner and went to the hotel owner, where he would sleep in the lounge, asking for 5 rupees to travel. The hotel owner was a compassionate man, gifted Allamah Saʿīdī 5 rupees so that he could travel to the seminary.

Allamah Saʿīdī’s seminary education

Arriving early at the seminary, Allamah Saʿīdī entered the tutelage of Shaykh ʿAbdul Majid Owaisi. The Shaykh taught him fundamental books on Persian and Arabic. Allamah Saʿīdī studied under the Shaykh for almost two years. There was a village nearby the seminary and the people, who were very poor, had a built a very small mosque and had requested the seminary if one of the students could come to lead prayers and teach Qurʾān to the children. In return they would provide two meals a day, and a few rupees a month. Allamah Saʿīdī took this position on. He would clean the mosque, collect water from the well for others to do Wuḍu, teach children and lead the prayers. In return he would be provided with two meals a day and a few rupees a month. Some months he would receive no money at all. Whilst carrying out his duties at this mosque he was visited by a student from the Jamia Naemiya seminary in Lahore. The student, who was passing by was amazed by the dedication of Allamah Saʿīdī urged him to travel to the seminary in Lahore for further education. Allamah Saʿīdī became perplexed at this situation. He thought to himself how he would go about asking his teacher for permission, as it may offend the Shaykh. After four days of thinking, Allamah Saʿīdī asked the Shaykh, who was more than happy for him to go. Allamah Saʿīdī now faced financial burden of travelling to Lahore. As he was sat in the mosque thinking, a man came with a goat asking if there was anyone poor who was worthy of taking this goat. Allamah Saʿīdī jumped at this opportunity explaining his dire need, took the goat and sold it. He bought a ticket and travelled straight to Lahore for one purpose: education.

In Lahore, Allamah Saʿīdī enrolled into the famous Jamia Naemiya seminary.3 He studied books such as Kāfiya, Sharḥ Tahzīb, Usūl Shāshī and Nūrul Anwār under Shaykh ʿAbdul Ghafoor. Under the tutelage of Mufti Hussain Naemi he studied Sharḥ Jamī, Qutbī, Tafsīr Jalālain and Hidāyatul Ḥikma. He also studied under Mufti ʿAzīz Ahmad Badāyūnī.

Mufti Hussain Naemi, the principal of the seminary was also an important figure at the ministry of religion. He was sent on training by the ministry for a whole year so the Mufti appointed Allamah Saʿīdī as his successor so that he would teach the classes in his absence. Allamah Saʿīdī was teaching a class on Sharḥ Tahzīb when a scholar named Imādud Dīn entered the class. He asked a few questions on logic to which Allamah Saʿīdī responded. After the students had gone Imādud Dīn asked Allamah Saʿīdī how he came to know the answers to such questions. Allamah Saʿīdī responded that although he had answered the questions, he felt that he did not respond adequately. Imādud Dīn praised his intelligence and advised him to strengthen his studies in logic and Kālām by studying under the erudite scholar ʿAtā Muhammad Bandyālwī.4 Allamah Saʿīdī took permission from Mufti Hussain Naemi to go to Bandyāl Sharīf to further his study. Permission was granted under the condition that Allamah Saʿīdī would return to Jamia Naemiya seminary to teach. Allamah Saʿīdī stayed under the tutelage of ʿAtā Muhammad Bandyālwī for three and a half years. He studied Jāmʿi Tirmiḏī, Mishkat al-Masābīḥ, Tawḍīh Talwīh, al-Hidāyah, Muḫtasar al-Maʿānī, Shams Bāziġa, Qāḍī Mubārak, Ḫiyālī, Musalam al-ṯabūt amongst other books. Whilst studying here he faced many hardships. He would eat one roti whilst soaking it in water.

Allamah Saʿīdī also travelled to the Jamia Qādiriya seminary to study under Maulana Walī al-Nabī and Mufti Mukhtar Haq. He studied Sirājī and other books. Whilst studying, Allamah Saʿīdī faced many hardships however due to his strong conviction he overcame these. In his student days, he would often spend the nights preparing for the following day’s lessons. When he was told that the classes had been cancelled, he would often cry. He only owned a few set of clothes.

In 1958, Allamah Saʿīdī gave his spiritual allegiance to Allamah Sayyid Aḥmad Saʿīd Kaẓmī.

Some of the books studied by Allamah Saʿīdī in amia Naemiya seminary

Allamah Saʿīdī’s teaching career

Allamah Saʿīdī began teaching in 1966, after completing his studies he immediately began teaching at the Jamia Naemiya seminary, Lahore. At the beginning his teaching was limited, however as his popularity grew amongst students, his teaching increased. In a few years, he began teaching the Dowra Ḥadith classes. He taught in this seminary until 1985. Whilst teaching in Lahore he began writing.

He wrote his first article whilst a student on ‘Ala Hazrat Ka Fiqhi Maqam’ (Imam Ahmad Rida Khan’s station as a Jurist). In 1979, he published his first book titled ‘Tawdīhul Bayān.’ He had a brief break in 1979, when he left for Karachi. Later in 1980 he returned to teach. In 1986, his health deteriorated so he left for Jamia Naemiya in Karachi upon the request of Muftī Sayid Shujāʿat ʿAlī. He was appointed as the Shaykhul Hadith. He was only required to teach around one hour a day. This freed his time up for writing. In Karachi, he wrote his most famous of books. A commentary on Saḥīh Muslim titled ‘Sharḥ Saḥīḥ Muslim.’ A commentary (tafsīr) titled ‘Tibyānul Quran’ and a commentary on Saḥīḥ Bukharī titled ‘Ni’matul Barī’.

As a teacher, he was dedicated to teaching and writing. On a particular occasion, his students enquired how he was to which he replied, ‘My son, for the past four hours I have been sifting through books looking for a reference. Pray to Allah ﷻ that I find it.’ Allamah Saʿīdī never married.

Allamah Saʿīdī’s demise

Allamah Saʿīdī became very ill in his last days. Mufti Muneebur Rehman insisted that he should go to the hospital, however Allamah Saʿīdī was determined to carry on working and writing. He often stated his wish was to die whilst writing Quran and ḥadīth. He became very unwell so he was transferred to Aga Khan hospital in Karachi. Allamah Saʿīdī had a tumour which was treated by the doctors. He was then transferred to the ICU and put on a ventilator. Allamah Saʿīdī requested his students to recite Sura Yasīn, Salawāt and read Istighfār. He told them to bring his Tafsīr, Tibyānul Quran and read the introduction of Surah Yasīn in which it states that whoever recites Surah Yasīn whilst facing death, Allah ﷻ would ease the pangs of death for him. Allamah Saʿīdī remained in ICU for 6 days and then passed away on Thursday 4th February 2016. His funeral prayer was led by Mufti Muneebur Rehman in Karachi after the Friday prayers, and thousands of scholars, students attended his funeral prayer.

Allamah Saʿīdī’s teachers

In this section, I explore the influential teachers who played a crucial role in shaping Allamah Saʿīdī’s educational journey. Recognising the profound impact teachers have on students’ character and vision, I highlight the significance of Allamah Saʿīdī’s access to some of Pakistan’s greatest scholars.

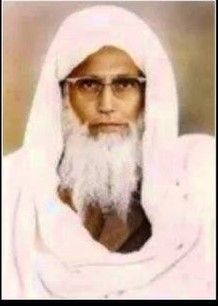

Allamah Sayyid Aḥmad Saʿīd Kaẓmī

He was born in 1913 in Amroha (India). He is a descendant of Imam Mūsā Kaẓim. His father Sayyid Muḥammad Muḫtār Kaẓmī died whilst he was young. He was nurtured and educated by his elder brother Sayyid Muḥammad Ḫalīl Kaẓmī and completed his studies at the age of eighteen. He began teaching whilst he was a student. His teaching started at the Jamiʿa Nuʿmāniya seminary in Lahore. He then returned to Amroha where he taught at the Muḥammadiya Hanafiya seminary. He then travelled to Okara and taught for a year there. In 1935, he went to Multan and began teaching at his house. He also gave sermons on the exegesis of the Quran at the Hāfiz Fatḥ Sher Mosque once a week and completed the entire Quran in eighteen years. He also gave sermons on Bukhari and other Hadith books. He was attacked in a village in Bahawalpur whilst giving a talk due to which he stayed in hospital for six months. He was very prominent and vocal for the movement of Pakistan and attended the famous Banaras conference in 1946.5 He served as a Hadith lecturer at the Bahawalpur Islamic University for over ten years. He is known by his famous accolade Ghazālī Zamān (The Ghazālī of the Era). He authored 19 books:

Tasbiḥ al-Rahman ʿAn al-Kizb wa al-Nuqsan

Glorifying the Merciful: Free from Lies and Deficiencies

Muzilat al-Niza Fi Iṯhbat al-Samāʿ

Resolving Disputes on the Acceptance of Listening (to Spiritual Music)

Taskin al-Khawātir

Calming the Thoughts

Hayat al-Nabi

The Life of the Prophet

Miʿraj al-Nabi

The Ascension of the Prophet

Milad al-Nabi

The Birth of the Prophet

Taqrir Munir

A Clear Explanation

Hujiyat ḥadith

The Authority of Hadith

Islam Aur Isaʾiyyat

Islam and Christianity

Mukalama Kazmi wa Mawdudi

Dialogue between Kazmi and Mawdudi

Taḥqīq Qurbani

The Study of Sacrifice

Nafi al-Zil wa al-Fai

Refuting the Idea of Shadow and Reflection

Kitab al-Tarawih

The Book of Tarawih

Al-Haq al-Mubīn

The Clear Truth

Al-Tahrir

The Explanation

Al-Taqrir Sharh al-Tahrir

Commentary on Al-Tahrir

Islam aur Socialism

Islam and Socialism

Tulaba Ka Islami Kardar

The Islamic Character of Students

Al-Tabsir Bi Rad al-Taḥzir

Clarifying the Rebuttal of the Prohibition

“The Ghazali and Razi of his era, Allamah Sayyid Aḥmad Saʿīd Kaẓmī was a great Jurist and Hadith scholar who served his life as a Hadith scholar. He wrote many valuable treatises on different theological topics. He was a man of his time who possessed leadership qualities such that he could lead the nation religiously and politically” (Allamah Saʿīdī)

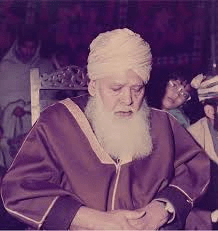

Allamah ʿAṭā Muḥammad Bandyālwī

He was born in 1916 and his lineage traces back to Hazrat ʿAlī (may Allah be pleased with him). After memorising the book of Allah ﷻ he spent ten years studying traditional sciences under great scholars such as Qaḍī Muḥammad Bashīr, Mawlānā Yār Muḥammad Bandyālwī, Hafiẓ Mehr Muḥammad Acharwī, Mawlānā Muḥibu-nabī and others. His spiritual oath was given to Pīr Sayyid Mehr Alī Shah.

Allamah Bandyālwī began teaching once he completed his education. In 1943, he taught at Hizb al-Aḥnāf seminary for a year. In 1944, he taught at the Islamiyya Reḥmāniya seminary in India. He then travelled to Bhera Sharīf where he taught for 3 years. On the invitation of Khwaja Qamaruddin Siyālvī he taught at the ḍiya Shams al-Uloom seminary for 8 years. He then taught at the Maẓhariya Imdadiya seminary in Bandyāl Sharīf for 25 years. He spent most of his teaching career there, which is why he is known as Bandyālwī. In total, he taught at 11 different seminaries for over 50 years. Thousands graduated at his feet. Reflecting on his students Allamah Bandyālwī remarked, ‘I have taught for over 50 years and produced students in great masses. I take great satisfaction that have produced 50 students who are able to convey the message to forth coming generations. They include Mawlānā Allah Baksh, Mawlānā Ghulam Rasul Saidi, Mawlānā Ghulām Rasūl Riḍawī, Mawlānā Muḥammad Ashraf Siyālwī, Mawlānā Muḥammad Rashīd Kashmīrī, Mawlānā ʿAbdul ḥakīm Sharf Qādrī and others.’

Allamah Bandyālwī style of teaching was unique as he was well-versed in the Khayrabadiya6 tradition. He would first ask the students to read the Arabic text. Whilst listening he would point out grammatical mistakes. He would then unlock these difficult texts by discussing deep theological points. He would then ask the students to summarise what he had explained. If Allamah Bandyālwī was not satisfied with the student, he would repeat his explanation and test the student again.

Allamah Bandyālwī was also politically active. He was part of Muslim League and took the message of Pakistan to every household. He was also part of the Jama’iyat Ulemah Pakistan and remained as a convener and vice convener. He passed away in February 1999.

Allamah Bandyālwī authored 28 books:

Sayful ‘Ataa

The Sword of Generosity

Ruyat Hilal Ki Shar’i Tahqiq

Islamic Ruling on Moon Sighting

Diyatul Mara’

The Blood Money of a Woman

Masla Haḍir & Nazir

The Issue of the Prophet’s Presence

Qawwali Ki Shar’i Hasiyat

The Islamic Ruling on Qawwali

Aqidah Ahle Sunna

The Belief of the Sunni Community

Islam Mein Aurat Ki Humarani

The Role of Women as Leaders in Islam

Masla Imamat Kubra Aur Us Ke Sharait

The Issue of Leadership (Imamat) and Its Conditions

Darse Nizami Ki Zuroriyat Aur Ehmiyat

The Importance and Necessity of the Darse Nizami Curriculum

Sarf ‘Ataee

A Study on Arabic Grammar (Etymology)

Safarnama Baghdad

A Travel Diary of Baghdad

Tahqiq Iman-e Abu Talib

An Inquiry into the Faith of Abu Talib

Al-Tahqiq al-Farid Fi Taraakeeb Kalimah Tahweed

A Unique Study of the Structure of the Testimony of Faith

Tahqiq Waqt Iftaar

An Inquiry into the Time for Breaking the Fast

Mah Siyam Aur Ba Jamat Namaz-o-Witr

Performing Witr in Congregation During Ramadan

Masla Sood

The Issue of Interest

Azan Se Kabl Aur Ba’ad Durood Sharif Ka Bayan

Sending Salawat Before and After the Azan

Hudood Ki Sazao Ke Nifaz Ke Liye Aurtoo Ki Shahadat Ka Hukm

The Ruling on Women’s Testimony in the Implementation of Islamic Penal Punishments

Shan-e-Awliya

The Greatness of Allah’s Friends (Saints)

Nizaam ‘Adl Aur Fiqh Hanafi

The Justice System in Hanafi Law

Jihad Ki Ahmiyat

The Importance of Jihad (Struggle)

Siya Khidaab

The Issue of Black Dye

Tasweer Ki Shari’ Haysiyat

The Islamic Ruling on Pictures

Masla ‘Ilm Ghayb Nabi ﷺ

The Issue of the Prophet’s Knowledge of the Unseen

Masla Noor Aur Bashr

The Issue of the Prophet Being Light and Human

Shan-e-Wilayah

The Greatness of Spiritual Authority

Masla Kizb

Refuting the Claim That God Can Lie

“My great teacher, Mawlānā ʿAṭā Muḥammad whose love and affection has given me the respect that I get today. Due to his immense knowledge, many became stars of this nation. It was his teaching and education, that I am able to teach, read and write. Even today, those who want to quench their thirst of knowledge, run to his fountain.” (Allamah Saʿīdī)

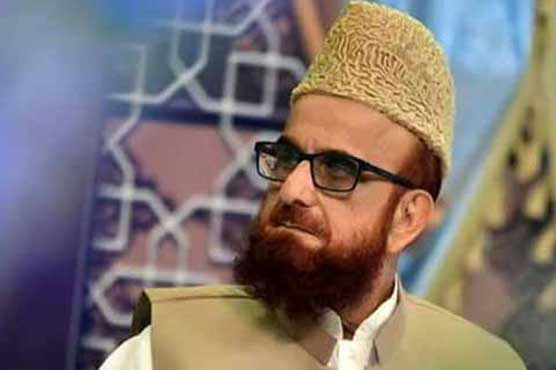

Muftī Muḥammad Hussain Naʿīmī

Many major Barelvi figures studied under him and adopted the epithet ‘Naemi,’ derived from his name

Muftī Hussain was born in India in 1923. He studied at the famous Jamia Naʿīmiya seminary in Muradabad. His teachers include Mawlānā Shamsul Haq Bihari, Muftī Amīnudīn, Muftī Aḥmad Yār Khan, Muftī Muḥammad ʿUmar and Sadrul Afāḍil Mawlānā Naʿīmudīn Murādabādī.

Muftī Hussain began teaching the Hizbul Aḥnāf seminary in 1941. After teaching for 6 years he left for Jamia Nʿumaniya seminary in Lahore. He taught at this seminary for 6 years. In 1962, he was appointed as the District religious minister. However, he was dismissed as he did not agree with government policies. He laid the foundations of the Jamia Naʿīmiya in 1953. Due to his knowledge and dedication, a number of students began to increase so he moved to a campus in 1958 where he further developed the seminary.

He was politically very active and was very passionate for the cause of Pakistan. He joined Muslim League and fervently pushed for the creation of Pakistan. He was also part of the Sunni and Shia Peace Committee and he served as a convener in 1954. He fulfilled this role under the guidance of Allamah Sayyid Aḥmad Saʿīd Kaẓmī.

“Allamah Muftī Hussain Naʿīmī was a great scholarly and political figure who is well known in Pakistan. He always dealt people with wisdom. He was never confrontational with others, rather polite.”(Allamah Saʿīdī)

Allamah Saʿīdī’s works

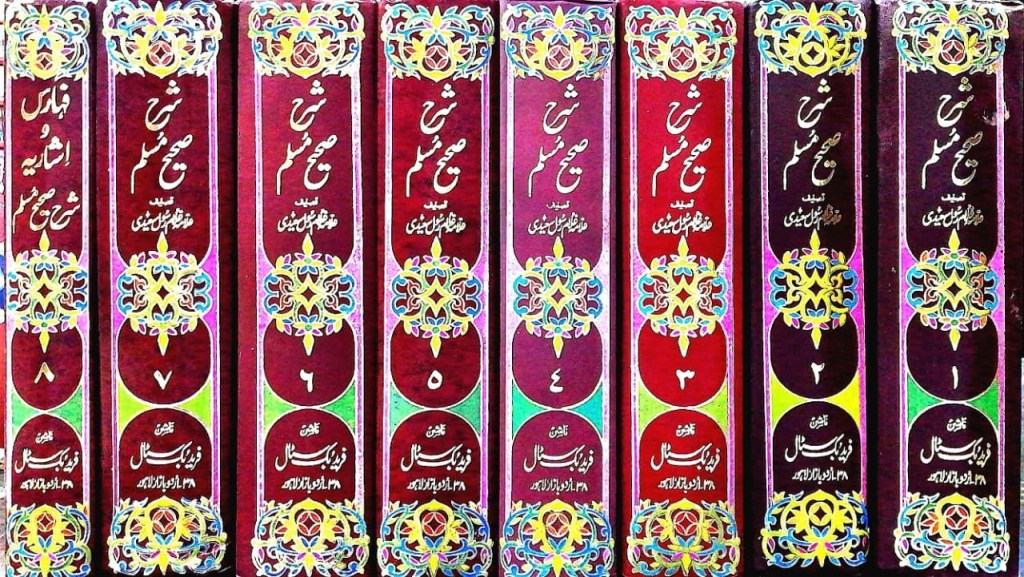

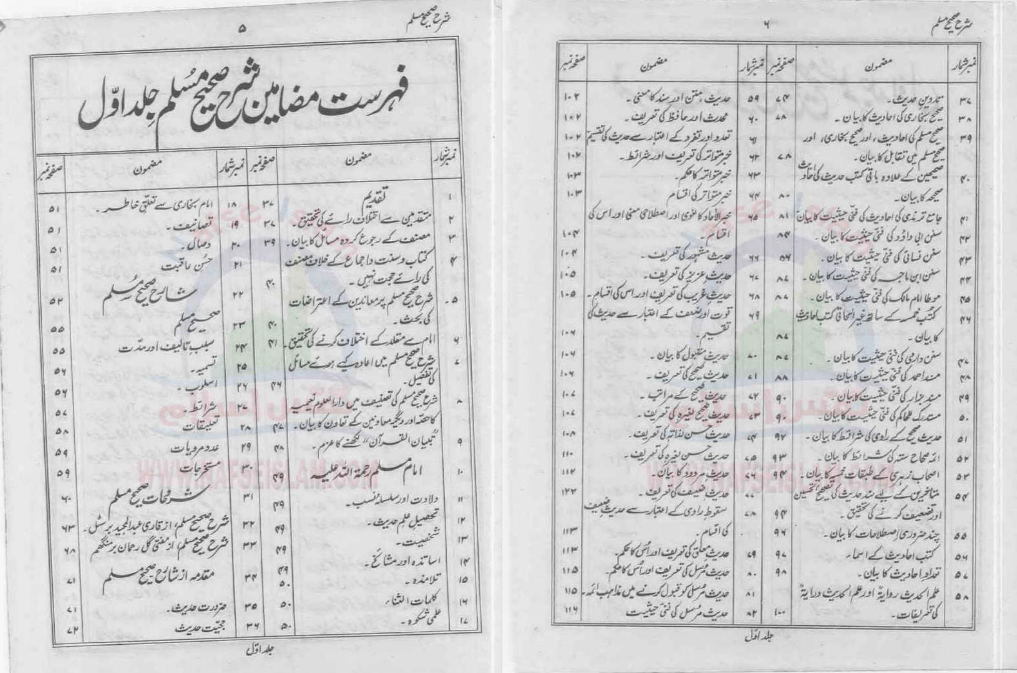

Sahih Muslim Commentary

Allamah Saidi’s commentary on Sahih Muslim

He began his magnum opus in 1980. However due to illness he left it for four years and began work on it in 1986, completing it in 1994. This work consists of 8 volumes, spanning over 8 thousand pages.

He commences this work with a thorough biographical exploration of Imam Muslim, detailing his life, scholarly pursuits, and contributions to hadith literature. Following this, he delves into the significance of Sahih Muslim within the Islamic tradition, detailing the various commentaries that have been authored on Sahih Muslim throughout history. Subsequently, he allocates 200 pages to an in-depth discussion on the science of hadith.

He begins this great work by introducing each chapter of Sahih Muslim. He translates the Hadith into Urdu and then comments on the hadith, relying on previous commentaries. If the hadith is related to law, he explains the opinions of all four schools, giving preference to the Hanafi School. The outstanding feature of this work is that he tackles modern fiqhi issues in a very profound and well-grounded manner. His mastery of the legal source’s manifests throughout this work.

I have chosen to translate a portion of Allamah Sa’idi’s introduction, which demonstrates his integrity as a scholar. It highlights his commitment to producing original research and his strength in facing criticism from his contemporaries.

‘To differ with the earlier community of scholars and jurists’.

We confess that the previous scholars who preceded us are all held in high regard due to their status and honour. However, they were people like us and not Prophets, so they did make mistakes. Apart from Prophets, whether it be a scholar, a man of deep spiritual insight, or a great lover of the Holy Prophet ﷺ, he is fallible, and considering such a person’s work as infallible is apostasy, as it elevates the rank of such a person to that of a Prophet (and we seek refuge in Allah from this). Ibn Abidīn writes,

‘There is a consensus among the scholars regarding the Kufr of Pharaoh. However, Ibn ʿArabī opposed this consensus. Ibn Hajr states that although we have great respect and admiration for Ibn ʿArabī, we reject this opinion of his because infallibility is reserved only for Prophets.’

Haskafī states, ‘Allah has negated infallibility for all books apart from His (i.e., the Quran).’

Ibn Abidīn also confirms this by stating that Allah has declared infallibility only for the Quran. He states in the Quran, ‘It cannot be approached by falsehood, neither from its front nor from its behind. A revelation from the All-Wise, the Ever-Praised.’ Therefore, apart from the Quran, all other books have mistakes and shortcomings, because they are the works of men and not of the Almighty. ʿAbdul ʿAzīz Bukhārī, in his commentary on Usūl Bazdawī, writes that Buwaiṭi relates from Imam Shafʿī that when he completed his book ‘Risālah’, he remarked, ‘Take only that which complies with the Quran and Sunnah, and leave the rest.’ Imam Muzani says that he read the ‘Risālah’ to Imam Shafʿī over eighty times, each time the Imam would highlight mistakes. The Imam then said to Muzani to stop, for Allah only guarantees the Quran to be free from all types of mistakes and errors.

In my commentary on Sahih Muslim, I disagreed with certain scholars, providing evidence for my disagreement. However, some people have made me a target for their criticism, as they feel I should not have disagreed with earlier scholars. They question by saying, ‘Didn’t the early scholars know of these evidences, are you the only one who knows them?’ These are baseless accusations, for when a person researches a topic, disagreement does arise from time to time. After all, those earlier scholars also disagreed with their predecessors on certain issues, who disagreed with their predecessors. I ask, ‘Did they have more knowledge than their predecessors? Weren’t their predecessors aware of these evidences?’ This disagreement can be traced right back to the earlier generations of the Sahabah and Tabiʿīn.

Muslim Scholars discussing matters of law

When the time of death came near for the caliph ʿUmar, Suhaib began to cry, and ʿUmar chastised him for that, stating, ‘You are crying for me, when you well know that the Holy Prophet ﷺ mentioned that whoever cries for a deceased, the deceased feels pain due to that crying.’ Ibn ʿAbbās states that when caliph ʿUmar passed away, I went to the mother of Believers, Aisha, and asked her to explain what ʿUmar had said. She replied, ‘May God’s peace be on Umar, (as for his statement about the deceased being punished) it was in regard to the enemies of the Prophet. For us Muslims, it is sufficient what the Almighty states in the Quran, “No one will bear the burden of someone else.”‘ This example illustrates the dignity of difference. Lady Aisha disagreed with ʿUmar despite ʿUmar being superior to her in knowledge. However, she disagreed with valid evidence, and this disagreement did not hinder ʿUmar’s station of being more learned. Based on this, we understand a principle that a scholar of less intellectual ability can disagree with someone who is superior to him as long as he presents evidence for his disagreement. Mulla Ali Qari, quoting this entire incident from Ibn Hajr, states that some Shafi’i scholars of my time are still bound to the shackles of Taqlid and have not understood the process of Tahqiq, for each time I differ with Ibn Hajr, they say to me, ‘How can someone like you disagree with Shaykhul Islam Ibn Hajr, who was from the great mountains of knowledge!’ Whereas Ibn Hajr himself accepts that Lady Aisha disagreed with Caliph Umar.

Likewise, many scholars after Imam Abu Hanifa disagreed with him. For example, Abu Hanifa stated that the six fasts of Shawwal are disliked, however, because the many hadiths that highlight the excellence of these fasts didn’t reach Imam Abu Hanifa, later scholars disagreed with him. ʿAllamah Amjad Ali has also stated that these fasts are recommended. Imam Ahmad Rida Khan, a great scholar, also disagreed with Imam Abu Hanifa. For example, in regards to the بيع العينة (a particular type of credit sale in Islamic finance), the hadith disapprove of such a transaction, and based on these traditions, Imam Malik, Imam Ahmad, and Imam Abu Hanifa declare such a transaction prohibited whereas Imam Ahmad Rida Khan allowed these transactions and spoke of their merits. Similarly, Imam Abu Hanifa and his students Qadi Abu Yusuf and Imam Muhammad declared that the Aqiqah (sacrifice) was disliked, whereas later Hanafi scholars stated that Aqiqah was Sunnah. This was because Imam Abu Hanifa and his students didn’t come across the Hadith that mention the excellence of Aqiqah. Imam Muhammad states, ‘We investigated and took the hadith of Lady Aisha which stated that Aqiqah was the practice of the days of ignorance. When Muslims began to sacrifice animals on Eid, Qurbani abrogated all previous sacrifices. Similarly, the fasts of Ramadan abrogated all previous fasts.’ This is also stated by Kasani.

Finally, I’d like to say that it is clear from these previous examples that when differences occur between scholars, the personality of an individual is not employed as evidence, rather it is the textual proof which is provided. My advice to those who only look and compare personalities, please stop acting like the jury, as if you have set up a court determining who is better. Are you so great that you’re able to compare two great scholars?7

Quran Commentary

Allamah Saidi’s commentary on the Majestic Quran

Allamah Saidi began work on his Tafsir of the Quran in 1995 and completed this extensive work in 2005, which spans over 11,000 pages across 13 volumes. The work begins with a lengthy introduction and history of the Quran, covering 139 pages. The commentary on the first chapter of the Quran, Surah Al-Fatiha, extends over 100 pages, and was translated into English by my teacher, Dr. Ather Hussain Al-Azhar.

Allamah Saidi consulted over 264 works in the course of writing his Tafsir. He writes, “During the compilation of Tibyan al-Qur’an, the author greatly benefited from the commentaries of Imam Razi’s Tafsir al-Kabir and Tafsir al-Qurtubi’s Al-Jami’ li Ahkam al-Qur’an. After them, the author further reinforced his work by referring to Ruh al-Ma’ani. He has consulted all the authentic commentaries that are available. Among them, Allama Jalal al-Din al-Suyuti’s Al-Durr al-Manthur has also been extensively utilised. The Tafsir of Imam Abu Mansur Maturidi was published while I was writing the 12th volume of Tibyan, and I benefited from it as much as I could.

In Tibyan al-Qur’an, it was my desire to extensively use the Hadith and sayings of the Sahabah, just as the Mufassirun before me have done. However, the unique aspect of my work is that all Hadith have been fully referenced with detailed citations and Takhrij (verification of authenticity). It is natural that, when one writes, they may disagree with others, and in many cases, the Mufassirun have disagreed with previous scholars on certain meanings and interpretations. However, wherever I have differed, I have maintained the utmost respect and adherence to proper ethics.

The second significant feature of this Tafsir is that I have written it in simple and plain Urdu, which is why this Tafsir has gained so much popularity. As the world evolves, so do my own viewpoints. Even as Tibyan al-Qur’an and Sharh Sahih Muslim have been published, I continue to update them. However, these updates are not substantial.”8

An English translation of Razi’s Tafsir

Regarding Razi’s Tafsir, Allamah Saidi writes, “Tafsir Kabir is the monumental work of Imam Fakhruddin Razi, a leading theologian and renowned commentator (Imamul Mutakallimeen and Sanadul Mufassireen). His Tafsir is well-researched and highly respected by scholars. While it holds particular importance for the Shafi’i school, compared to the Hanafi school, it serves as a strong defense for Ahl al-Sunnah against deviant sects. Its scholarly significance is widely acknowledged.

In this Tafsir, Imam Razi devotes much of his effort to refuting the Mu’tazilites, using a highly philosophical and logical approach. He also counters materialist views in matters of belief. When it comes to fiqh (Islamic law), he favored the Shafi’i school, often presenting Hanafi arguments, especially those found in Ahkam al-Qur’an by Imam Jassas, and then refuting them with his own evidence.

Razi’s Tafsir shows a deep reflection on the verses, bringing out unique insights. For the context of revelation (Asbab al-Nuzul), he relied on Tafsir Tabari and Tafsir Wasit, and for matters of eloquence (Balaghah), he often referenced Zamakhshari’s Al-Kashshaf. Throughout his work, Razi expresses profound reverence for the Prophet (PBUH), the Ahl al-Bayt (the family of the Prophet), and the Companions, using highly respectful language when speaking about them.

Sadly, Imam Razi was not able to complete this Tafsir. According to Allama Khafaji, he finished up to Surah Al-Anbiya. Haji Khalifa mentions that Najmuddin Qamuli later completed it. I have relied extensively on this Tafsir, and while I have the utmost respect for Imam Razi, I do differ with him on some points. These are as follows…”9 He extensively disagrees with Imam Razi and this is evident throughout the Tafsir.

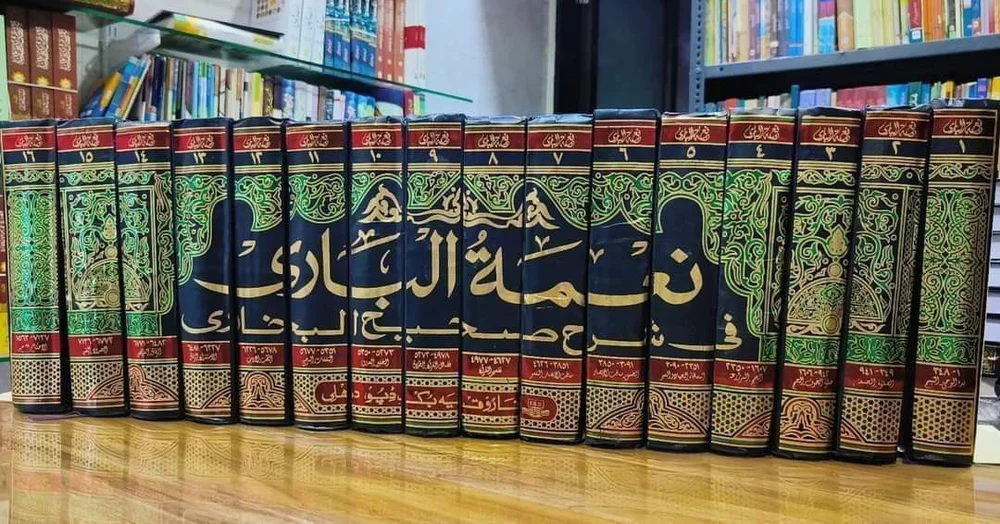

Sahih Bukhari Commentary

Allamah Saidi’s commentary on Sahih al-Bukhari

Allamah Saidi began his commentary on Sahih al-Bukhari immediately after completing Tibyanul Quran in 2005, and finished the commentary in 2012

Allamah Saidi begins his commentary on Sahih al-Bukhari with the Muqaddimah, which opens with a brief introduction to Hadith and its various types. He then provides a detailed account of the life of Imam Bukhari and follows with an in-depth discussion of Sahih al-Bukhari, including its commentaries, summaries, and related works. A total of 111 pages are dedicated to this section.

Praying on the train: Some scholars have stated that praying on a train is not permitted, while others have allowed it with the condition that the prayer must be repeated. However, Allamah Saeedi, in a detailed 10-page discussion, concluded that it is permissible to pray on a train or airplane while they are moving, and the prayer does not need to be repeated. His conclusion is based on four key points, supported by 33 references.

He writes:

- The Quranic verse from Surah Al-Baqarah (2:239) emphasizes the importance of performing prayer even in situations of fear or danger. The verse states:“If you are in danger, pray on foot or while riding.”This verse permits prayer while riding in cases of necessity, especially when trying to disembark from a moving train or airplane could risk one’s life.

- A Hadith from Tirmidhi is cited, where the Prophet ﷺ prayed on his mount due to the presence of puddles and mud, without dismounting. This Hadith sets a clear precedent for performing prayer while riding in difficult circumstances.

- He mentions the Ijma’ (consensus) of scholars, which confirms that if someone prays while riding due to a necessity, they are not required to repeat the prayer. This consensus strengthens the permissibility of such prayers in cases of genuine need.

- Qiyas (analogy) is drawn between modern modes of transportation—such as trains and airplanes—and traditional ones like ships and animal rides. Since praying on a ship or while riding an animal has historically been accepted, the same ruling applies to these modern forms of transport. Thus, praying on a train or airplane is permissible without the need to repeat the prayer.10

Similarly, Allamah Saʿīdī produces original research as he looks at other modern issues such as mortgages, interest, blood transfusions, organ donations, and more.

May Allah bless and reward Allamah Saʿīdī and all our traditional scholars for their tireless efforts in preserving, protecting, and expanding Islamic knowledge. May He elevate their ranks, grant them immense barakah in this life and the hereafter, and make their works a source of guidance for generations to come. O Allah, shower Your mercy upon them, strengthen the scholarship of our Ummah, and grant us the ability to benefit from their wisdom and remain steadfast on the path of truth, Al-Fatiha

- This article is based on the following works;

i. ‘Ni’matul Bari Ka Manhaj wa Aslub.’ MPhil dissertation by Shagufta Jabeen in which she discusses ʿAllāmah Saʿīdī’s commentary on Sahih Bukhari, Ni’matul Bari. She focuses on his methodology and how it compares to other commentators of Bukhari. Jabeen provides an extensive biographical introduction of ʿAllāmah Saʿīdī.

ii. ‘ʿAllāmah ġulām Rasūl Saʿīdī Ki Hayat-o- Khidmat’ was an article published in the monthly Zia-e-Haram magazine (Issue: March, 2016) by Shagufta Jabeen. The article discusses the final moments of ʿAllāmah Saʿīdī and gives a brief overview of his works. ↩︎ - Shaykh Muhammad Umar Icharvi (1901-1971) was the father of Shaykh ʿAbdul Wahhab Siddīqī (1942-1994), founder of the Hijaz college seminary in Coventry. Shaykh Umar Icharvi was one of Pakistan’s leading Sufi scholars of the time, who held the honorary title of Munazare-Azam (the greatest debater) because of his success in defeating the leaders of rival Islamic sects ↩︎

- Jamia Naeemia Lahore is a renowned Islamic educational institution that has made significant contributions to the promotion of religious sciences in Lahore, Pakistan. It was Established by Mufti Muhammad Hussain Naeemi. Following Mufti Muhammad Hussain Naeemi’s passing in 1998, Sarfaraz Ahmed Naeemi took over as the principal. After Sarfaraz Ahmed Naeemi’s death in 2009 due to a suicide attack, his son Dr Raghib Hussain Naeemi assumed the role of principal. ↩︎

- ʿAtā Muhammad Bandyālwī (1916-1990) was a distinguished scholar, celebrated for his exceptional proficiency in logic and rational sciences. His intellectual prowess and keen understanding in these fields marked him as a luminary in the scholarly community. Throughout his life, he contributed significantly to the advancement of knowledge, leaving an indelible impact on the realms of logic and rational thought. ↩︎

- The All India Sunni Conference, established in 1925, served as a significant organization representing Indian Sunni Muslims, particularly those associated with Sufism. It emerged in response to the secular Indian nationalism led by the Congress and the changing geopolitical dynamics in British India. The Conference became a prominent voice for the Barelvi movement, providing a platform for engagement with evolving socio-political landscapes. Led by influential Barelvi figures, it aimed to safeguard the interests of Sunni Muslims, contributing to the discourse on religious and community matters. The Conference played a crucial role in shaping the narrative of Indian Sunni Muslims and promoting the cultural and religious heritage associated with Sufism in British India. ↩︎

- The Khayrabadiya tradition is named after Fazl-e-Haq Khairabadi (1797-1861) who was a famous theologian and philosopher. He participated in the Independence Wars against in the British in 1857 and died on exile to Andaman Island. ↩︎

- p. 218, vol. 1, Sharh Sahih Muslim, Allamah Ghulam Rasul Saidi ↩︎

- p. 1056, vol. 12, Tibyanul Quran, Allamah Ghulam Rasul Saidi ↩︎

- p. 8, vol. 13, Tibyanul Quran, Allamah Ghulam Rasul Saidi ↩︎

- p. 407, vol. 2, Sharh Sahih Muslim, Allamah Ghulam Rasul Saidi ↩︎